hola hovito

January 25, 2009

another mic test that became a song, this time a cover of “hola hovito.” the blueprint has been my favorite rap album for as long as i have had a favorite rap album (excepting brief intermissions for people’s instinctive travels and paths to rhythm and reachin’ (a new refutation of time and space) which thinking about it now both probably would’ve sold more copies if they had shorter names) . it started being my favorite rap album back when i didn’t really like rap but wanted to have a favorite rap album so i could feel like i had diverse and liberal taste and it’s stayed my favorite rap album right on through me starting to like, liking, and loving rap. the first cd i ever bought with my own money was the soundtrack album for the remake of godzilla, which i bought solely for the puff daddy/jimmy page collab “come with me” which i still contend is fucking awesome, i don’t care what you say (there was also a decent jamiroquai song if i remember and that wallflowers cover of “heroes” which had some very pretty e-bow on it).

the union of classic rockish guitars and rap has always interested me — i wrote a really swell paper on it in college, talking about ways rap producers sample classic rock. my opening posited “walk this way” as this sort of perfect harmony between the two genres (i.e. in parts the riff is sampled and scratched but in parts joe plays live lead, the shared vocals etc.). then i compared the use of the “when the levee breaks” drum sample in the beastie boys song “rhymin and stealin'” and the dr. dre song “lyrical gangbang” (and also some coup song i can’t even remember) — how the beasties, irreverent as they are, were so respectful of this sample (allowing it sections where it’s playing by itself) whereas for dre it’s just one element of the composition (alongside bongo drums!) and besides dre’s goal is a “lyrical gangbang,” not a musical one. the main thread of the essay after that (i don’t think it had a proper thesis statement, i sucked at that always) was how rap producers sampling classic rock were reversing the power/exploitation dynamic from white musicians stealing from black roots music to create rock and roll (i think i talked about elvis and the jimmy page lawsuits, i don’t know, i lost the paper) . one of the examples i used for that part was the sample of the doors’ “five to one” on the blueprint‘s “takeover,” the sort of disembodying/looping of jim morrison’s voice and also the “fame” part and how totally wimpy the guitar sounds when compared to the bassline.

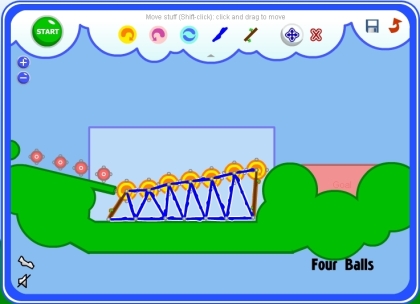

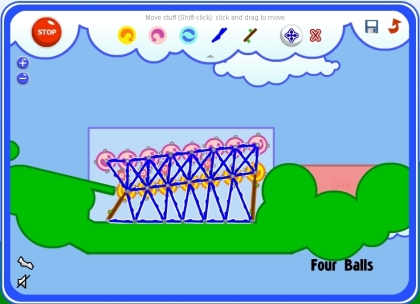

“the takeover” isn’t one of my favorite songs on the blueprint. like everybody else, i’m a sucker for the sped up soul samples and those are the ones i like best because they just make you feel good, grown and sexy and shit. for a long time i would skip “hola hovito” and it was probably my least favorite song on the album (well, besides that eminem song which i just deleted from itunes). now i don’t understand how stupid i was and i listen to it all the time. the production is amazing — like, it’s graceful and sonically experimental and so complex but also a total banger. it’s like if “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” were really true, like if muhammad ali was also baryshnikov (and also martian). obviously i couldn’t even try to come anywhere near tim’s production so i just tried to do the garage rock version of the song (i did take something from a youtube video i saw of i think him and kanye layering different kicks on top of each other and so i doubled the drum tracks in the choruses with a 909). my flow is also really weak and i guess i’m just really riding the white indie boy novelty thing — i could definitely do this song better but i was doing it without listening to the song but just reading lyrics and basing the performance on memory (i still couldn’t figure out the rhythm on the last couple lines so i cut them) and it’s a first take and i only really nail the feel in the second verse and whatever, why am i making excuses, this shit isn’t rock band, i don’t get a score.

p.s.

January 23, 2009

after making that last post, i’m pretty sure my rss feed for google reader (and possibly other feed readers) didn’t show this massive post i did a couple of weeks ago. if you didn’t see it (believe me, you would have noticed), you can read it here.

fe4ev00

January 23, 2009

i just got a new guitar yesterday! i haven’t had an acoustic guitar in a year and i haven’t had a nylon string ever. it’s awesome. so today i wanted to record something to test it and the new microphones i also got. i quickly got on this kind of grizzly-bear-ish fingerpicking thing and decided to go with it. the lyrics are basically cliched hipster criticism but i think there are some funny details (organic oatmeal stout) and i like the hooks at the middle and end. the hating for the singer-songwriter revivalist thing is mostly just a pose – i really liked all of that bon iver album and i really liked parts of grizzly bear’s album and i really like, well, um, one song by fleet foxes. but like i said, the lyrics were a strictly first draft sort of thing. i think they were inspired by my memories of that this american life story about the city guy who wanted to be a farmer but was too lazy and also that new york times story from a while ago about hipster farmers (i am too lazy to look up links for these). at one point there was a dig at michael pollan but i couldn’t rhyme anything with pollan but “fallin'” so i cut it for the found joke. i do genuinely hate indie beards but i think that might partially be because i can’t grow one and i resent not having the option. i wanted to do some big harmonies but i couldn’t make my first couple attempts work so i just added the mellotron strings. i’ve been working on long writing projects lately and it was really nice to just start and finish something in one sitting

dancing w/r/t architecture

January 13, 2009

“Start every post with a good first sentence that describes the story you are going to tell. Assume your reader won’t get past the first paragraph.”

“Don’t be too wordy. HuffPo says that 800 words is the outer-length limit for a blog post; anything longer will turn people off.”

“Blog readers have neither the time nor the inclination to read between the lines; blogs aren’t literature.”

– from “how to blog,” by farhad manjoo, december 18th

i bought a copy of phillip roth’s everyman a couple of months ago because i thought it would fit in the inside pocket of a jacket that i had also recently bought. this is not because i was dying to read the book — i’ve never been much of a fan of roth except for a few pages of “goodbye, columbus” and most of operation shylock. at the time, though, i thought it would be really nice if i had a book that fit in my jacket pocket and this practical concern was taking precedence over taste. i don’t wear a messenger or book bag regularly and i’m not the kind of person to carry a book around because i think it looks awkward when i do it and it makes me walk even more unnaturally than i normally do, but then the problem is that there are a lot of times when i’m stuck in a situation where i’d like to have a book to read but don’t have a book because i think i look awkward carrying around a book and i don’t wear a messenger or book bag regularly. anyway, to make a long story short, when i got home, i found out the book didn’t fit in the jacket pocket by maybe half a centimeter, no matter how much i forced it, and i wept and cursed and threw it behind the bed. i still haven’t gotten around to actually reading it yet, not the whole thing, but i did start it one day when my internet stopped working for a couple of hours. at the end of the opening set piece, which describes the burial of the titular “everyman,” roth calls funerals “our species’ least favorite activity.”

i guess this is true, if it’s really a real funeral we’re talking about, the kind where you have to put on a suit and go to the funeral parlor and eat old people candy from silver dishes, the kind where you have to make hushed small talk with people you don’t know without the aid of alcohol. i’m generalizing here based on limited experience — i’ve only been to one funeral in my life, my grandfather’s, which took place during the thanksgiving break of my freshman year of college, a few days after i had turned eighteen. my grandfather’s death didn’t particularly affect me, partly because i’m generally a pretty unsentimental person but also because at the time i was fully in the grip of that particular blend of self absorption that afflicts college freshmen — everything in the world seemed new and possible and, if this was so, why worry about death? i didn’t cry at my grandfather’s funeral and i remember spending the funeral itself thinking about basically three things: 1) “oh god, this person i don’t know is going to talk to me and i don’t have anything to say to them, oh god” 2) being self conscious about the jacket my parents had bought me at a nearby outlet store at 10 PM the night before and which did not fit very well 3) thinking the paintings on the walls of the funeral parlor were strange — as i remember, they were all of flowers in vases and/or funeral urns and it seemed weird that you would need pictures of those in a funeral parlor when the real things were so readily available — it would be like if doctors had impressionistic renderings of tongue depressors and cotton balls hung on the walls of their offices. so yeah, at the funeral of my grandfather, who when he was alive i did really and truly love in warm, heartstring-tugging ways, i was basically playing out an episode of “seinfeld” in my head, complete with a “what’s the deal with that?” kind of internal monologue. some people would take not feeling things at the funeral of someone they loved as a symptom of something being deeply wrong with them, like zach braff in garden state when he had that time lapse scene of all the people moving around him on ecstasy but he was sitting on the couch not moving because of, you know, the crippling emotional void inside him. but i was and i am way too self absorbed for that sort of introspection and i would rather just write it up as a tragicomic anecdote that makes several dated pop cultural references and post it on my blog. anyway, all this is to say in a really longwinded and digressive way that maybe phillip roth is right, maybe funerals do suck (sorry if i can’t conjure his elegance).

but though real life brick-and-mortar funerals for close friends and relatives might well be “our species’ least favorite activity,” funerals in the larger sense are probably one of our culture’s favorite pastimes, even if we can’t admit that to ourselves. i don’t think i really need to explain this much — the society of the spectacle, the day john kennedy died, princess diana, “where were you when the towers fell?“, randy pausch, heath ledger, the continued success of the arcade fire, blah blah blah blah blah. i guess this sort of impulse is an example of the cultural machine supersizing some basic human phenomenon — in this case, funeral condolences — taking this small, private thing and making it public and filmed and commented and RSS fed. as an aside, the only real death that i can remember ever making me cry wasn’t my grandfather and it wasn’t my manager at my high school job who OD’d on crystal meth and who is the only other person i’ve really known who died (i’m lucky in this way). it wasn’t even someone i didn’t know but whose work i loved or cared about, like phil hartman or spalding gray. no, the only real life death that’s ever made me cry was the death of anna nicole smith. a lot of writers would imbue this statement with some kind of symbolic significance or use it to make a larger point about the culture or reality TV or whatever — i’m not doing that. i’m just saying it because it really did happen, i did cry, and i think it’s kind of weird. it’s weird because i knew then and i know now absolutely nothing about anna nicole smith besides those commercials for whatever weight loss thing she was selling and the fact that she had a high pitched and annoying voice. then and now, i had neither knowledge of nor interest in her. but despite this, on the day she died, i turned on the TV, flipped to CNN during the middle of their nonstop, wall-to-wall coverage of her death, saw that she was dead, and cried, for whatever reason. i’m not a crier by nature and i only cried for a few seconds: it wasn’t emotional, it was reflexive crying, like automatic sprinklers tripped off by accident. i still can’t explain why.

after david foster wallace’s suicide, everyone on the internet wanted to say nice things about him. this is a nice thing that nice people do when someone nice dies; everyone wants to say something nice about a nice dead person: how they liked him, why they liked him, what things they liked about him, various things he said or did or wrote that they liked, etc. most of the nice people who wanted to say nice things about david foster wallace on their blogs or comment sections or facebook walls maybe hadn’t read or maybe didn’t own any of his books or if they had read or did own something maybe they had forgotten it or maybe they were too lazy or busy to retype excerpts of the things they supposedly maybe really possibly sincerely loved. therefore, the majority of the nice people nicely posted excerpts from that widely circulated (and totally nice!) commencement speech that david foster wallace gave at kenyon college in 2005, the one where he starts by saying that he’s going to sweat except he uses the word “perspire” because he’s david foster wallace. it’s amazing how plastered over the internet that thing is: the kenyon speech is the fourth result that comes up when you search simply for “commencement speech.” this makes me think that if humans were destroyed by an asteroid tomorrow and left only the internet as a record of our society, the pale, bespectacled alien tasked with making a record of our literary culture would completely dismiss david foster wallace as an eckhart tolle kind of motivational speaker who had this really weird obsession with water and saying what it was over and over again.

it seems obvious if you’ve read any of his work (even if only that commencement speech) that david foster wallace was constantly struggling with what it meant to be a human being and, more than that, what it meant to be a good human being. it seems obvious that this struggle permeated both his personal life and his writing (in a structural device in his review of joseph frank’s dostoevsky, collected in consider the lobster, he makes this struggle completely literal, directly asking the reader, in the asterisked sections interspersed throughout the review, questions about what it means to be a human being and what it means to be a good human being.). he was a good guy, i’m not arguing that he wasn’t, no one is (well, besides john ziegler). but, as i’ve said, everybody on the internet already posted stuff about how nice and good and wise he was and i don’t want to be like everybody; i want to be an individual, i want to be an iconoclast, i want to sing the song of myself (when i did my own david foster wallace eulogy, only about 7 words of 2000 were actually about him). i don’t want to do what so many blog commenters did by writing “this is water” and clicking post and so extending his rhetorical flourish off into internet infinity — i want to make my own rhetorical flourish. so, instead of waxing rhapsodic about the tao of david foster wallace and how this is totally water, i’m going to post an example of him being kind of a dickhead. this is an excerpt from larry mccaffery’s interview with him in the review of contemporary fiction which accompanied the original publishing of his anti-irony manifesto, “e unibus pluram: television and u.s fiction.”

LM: But did Carver really do that? I’d say his narrative voice is nearly always insistently “there,” like Hemingway’s was. You’re never allowed to forget.

DFW: I was talking about minimalists, not Carver. Carver was an artist, not a minimalist. Even though he’s supposedly the inventor of modern U.S. minimalism. “Schools” of fiction are for crank-turners. The founder of a movement is never part of the movement. Carver uses all the techniques and anti-styles that critics call “minimalist,” but his case is like Joyce, or Nabokov, or early Barth and Coover—he’s using formal innovation in the service of an original vision. Carver invented—or resurrected, if you want to cite Hemingway—the techniques of minimalism in the service of rendering a world he saw that nobody’d seen before. It’s a grim world, exhausted and empty and full of mute, beaten people, but the minimalist techniques Carver employed were perfect for it; they created it. And minimalism for Carver wasn’t some rigid aesthetic program he adhered to for its own sake. Carver’s commitment was to his stories, each of them. And when minimalism didn’t serve them, he blew it off. If he realized a story would be best served by expansion, not ablation, he’d expand, like he did to “The Bath,” which he later turned into a vastly superior story. He just chased the click. But at some point “minimalist” style caught on. A movement was born, proclaimed, promulgated by the critics. Now here come the crank-turners. What’s especially dangerous about Carver’s techniques is that they seem so easy to imitate. It doesn’t seem like each word and line and draft has been bled over. That’s a part of his genius. It looks like you can write a minimalist piece without much bleeding. And you can. But not a good one. …

LM: I’ve always felt that the best of the metafictionalists—Coover, for example, Nabokov, Borges, even Barth—were criticized too much for being only interested in narcissistic, self-reflexive games, whereas these devices had very real political and historical applications.

DFW: But when you talk about Nabokov and Coover, you’re talking about real geniuses, the writers who weathered real shock and invented this stuff in contemporary fiction. But after the pioneers always come the crank turners, the little gray people who take the machines others have built and just turn the crank, and little pellets of metafiction come out the other end. The crank-turners capitalize for a while on sheer fashion, and they get their plaudits and grants and buy their IRAs and retire to the Hamptons well out of range of the eventual blast radius. There are some interesting parallels between postmodern crank-turners and what’s happened since post-structural theory took off here in the U.S., why there’s such a big backlash against post-structuralism going on now. It’s the crank-turners fault. I think the crank-turners replaced the critic as the real angel of death as far as literary movements are concerned, now. You get some bona fide artists who come along and really divide by zero and weather some serious shit-storms of shock and ridicule in order to promulgate some really important ideas. Once they triumph, though, and their ideas become legitimate and accepted, the crank-turners and wannabes come running to the machine, and out pour the gray pellets and now the whole thing’s become a hollow form, just another institution of fashion.

to this, all i can say is one thing: WTF, DFW? is this rant seriously coming from the someone as seemingly compassionate and understanding as the guy who showed us the view from mrs. thompsons, from a guy who could write things like those long, sad scenes of don gately slowly dying in his hospital bed or who could create a character a character as beatific and alyoshic as mario incandenza, but also make him real? is this from the guy who told us what water is? i just don’t get how he could be that person and also could be this dude, talking in such a harsh and ungenerous way about these stupid, evil “crank-turners.”

don’t get me wrong, i don’t discount that the phenomenon exists — far from it. there are certainly a million shitty, tone-deaf, empty, clumsy, ugly imitations of hemingway and joyce and carver and INSERT FAMOUS AUTHOR HERE, and this is just talking about literary fiction and not even considering genre and that‘s just considering writing and not the millions of shitty derivations of sonic youth and the beatles, kubrick and godard, picasso and monet. there is a vast sea of derivative crap out there which sucks hard — i am not arguing this.

my problem with david foster wallace’s notion of “crank turning” is that he seemed to think it’s based on motive or intent, that these people who are generating their little grey pellets aren’t trying to do something great, don’t think they’re doing something great, and are instead just consciously doing the bare minimum to get by because they’re in it for the money, praise, recognition, and sex (?). maybe i’m completely naive and stupid but i just don’t get how this could be true — it doesn’t square with any notion of art making i’ve ever experienced. MAYBE at the very highest levels of commercial art it could kind of sort of be possible in some very limited cases, like in cocaine-strewn hollywood boardrooms or thomas kinkade’s studio or what have you, but the fact of the matter is that the great majority of people who write or paint or draw or sing aren’t getting rich or famous off of their work. most writers aren’t “buying an IRA or retiring to the Hamptons” on the back of their self published POD novel or the paypal tip jar on their blog or the contributor copies they get from whatever tiny literary magazine deigns to accept their work. i’m aware that david foster wallace made these statements in the heady days of the ’90s when people were actually getting paid money for writing literary fiction (!), but still. david foster wallace was a math genius in addition to being a writing genius, so let’s think about it in terms of numbers: there is a very small amount of art that makes money for the artists who make it and there is a very large amount of art that, to one degree or another, sucks. there is some overlap between these two groups, of course, maybe a larger overlap than there “should” be, in a “perfect” world, but the fact of the matter is that most artists aren’t making any money at all or getting any recognition for their art. yet they persist in making it nonetheless.

MS: something came into my head that may be entirely imaginary, um, which seemed to be that the book was written in fractals?

DFW: expand on that.

MS: it occurred to me that the way in which the material is presented allows for a subject to be announced in a small form, then there seems to be a fan of subject matter, other subjects, and then it comes back in a second form containing the other subjects in small and then comes back again as if what were being described were — and i don’t know this kind of science — but it just, i said to myself, “this must be fractals!”

DFW: it’s — i’ve heard you were an acute reader. that’s one of the things that’s structurally going on. it’s actually structured like something that’s called a sierpinski gasket, which is a very primitive kind of pyramidical fractal…but it’s interesting, that’s one of the, that’s one of the structural ways it’s supposed to kind of come together.

MS: …what is a sierpinski gasket?

DFW: it’s would be almost — i would almost have to show you…but it looks basically like a pyramid on acid with certain interconnections between parts of them that are visually kind of astonishing and the mathematical connections between them are interesting.

MS: all i really know about fractals comes from an essay by hugh kenner who leapt up and said, “oh, pound did this.” and he was trying to suggest that the ways in which material is organized in poetry and elsewhere is extremely unsophisticated, that, that the patterns of disorder are much more beautiful than the patterns of order and equally discoverable. when you structure a book in this way, do you mean it to be discovered?

DFW: yeah, that, that’s a very tricky question…

once, in one of the writing workshops i took in college, this girl brought in a story which was a completely transparent imitation of lorrie moore’s “self help.” total crank-turning. despite the fact that it was basically a copy of the moore story (which had been part of our assigned reading the previous week, making it all the more obvious), there was some really great writing in it, resonant and powerful stuff, and in my back page critique, i scrawled something like, “i understand that you felt like you needed this to work with, that maybe you didn’t know how to start, but the writing you’re doing is too good to just be imitating somebody.” at the end of the semester, the professor held our last class in the english department’s favorite bar and everybody was getting drunk (or at least i was getting drunk and that made it seem like everybody was getting drunk) and the girl kind of caught me and pulled me aside on one of my trips back from the bathroom and told me how much my comment had helped her and given her confidence and i told her that every word of it was true. for the next hour or so, we rubbed up against each other in our hard-backed chairs in the middle of the class and i wrote a note in her moleskine notebook that i wouldn’t let her read and she gave me her phone number and said she’d be around all summer and i never called her and i actually had completely forgotten about her up until a minute ago when i was stuck writing this section and i got the idea to write this anecdote to get myself out of it.

(god, this is all turning into a brief interview with hideous me, except it isn’t even brief.)

the one common factor in all undergraduate writing workshops (or at least all the ones i took) is a lot of sucky, sucking, suck-filled work. david foster wallace is right, it’s an order of grey pellets with a side of crank-turning. in fact, a lot of the work sucked so much you couldn’t even tell what influenced it (maybe nothing!) but if it had achieved some level of competence and readability, the fact that it was derivative of palahniuk or delillo or tobias wolff often became readily apparent (i was no exception to this rule – my senior year, i published in our school’s literary magazine the best darn “cathedral” rip-off ever).

but the thing is, nobody intends to suck and nobody intends to be derivative — nobody wants those things. everybody wants to be a bright, original shining star and in order to write you have to believe that you are, even if just for a moment, you have to believe that what you are doing has the possibility to be good or great or else how can you do it, how can you fight your way through how hard it is? even if you start from a place of derivation or imitation, the creative process is so mysterious and difficult that it seems unlikely that you could copy something without putting a lot of yourself into it. in workshop, when people handed out the stacks of copies of their stories, there would be such desperation in their eyes, so much desire that people would read this thing they had made, that they had stayed up all night working on probably, and see it as great and brilliant and amazing and genius and original, that they would love it (i’m probably projecting a little here, but i think this is mostly accurate). most of these good people’s work would, in my opinion, completely suck, but that didn’t stop them from the feeling or the wanting, it didn’t make them crank turners. i mean, like, you don’t go into your local independent, fair trade coffee shop and witness scenes like this:

[writer 1 is sitting at a table in the independent, fair trade coffee shop, writing in a moleskine notebook. writer 2 enters the coffee shop and sets down his macbook air and an iced macchiato.]

writer 1: hey man, how’s the novel coming?

writer 2: oh, it’s great. i had this breakthrough this morning and in an hour, i wrote like 4 pages of completely derivative shit! i mean, it is sooo crappy, dude. i came up with this character and he’s a total rip off of stephen dedalus, like he’s really, really lame.

writer 1: wow, congratulations, dude, i can’t wait to read it.

writer 2: what about you, ezra? did you finish your poem?

writer 1: nah, i’m still struggling with it. the first draft had like this energy to it, it was so…facile…and…imitative. but now i feel like i’m losing that. it really sucks.

writer 2: sorry, man. you’ll get there, don’t worry.

[musician friend bursts in, carrying an ipod and portable speakers]

musician friend: guys, you have to hear this song i recorded, it’s a perfect note-for-note rip of “teen creeps”!

writer 1 + writer 2: awesome!

my last semester of college, i took this class in the theory and criticism of pop music. the reading list for the class was really cool – greil marcus, richard peterson, dick hebdige, the 33 1/3 book about zeppelin, some others. but much more interesting than what i learned in the class were the people who i learned it with. the class, more than any other i ever took in college, was crammed full of people who broadcast their personal taste as if from boomboxes lofted onto their shoulders. there were several kids who wore t-shirts from the college radio station to almost every class session and, in their clique, one particularly obnoxious guy who would make chapter and verse references to creem and crawdaddy (i both hated him and secretly wanted to be him, kind of the way i feel about almost famous). you could almost understand the class simply by haircuts — there were multiple emo razor jobs, long, unwashed stoner waves, hip hop heads in dreads (the guy) and a gele (one of the girls, occasionally), and even a guy who unironically wore an honest-to-god cowboy hat to class several times. in all four years of college, i never experienced such heated discussion as i did in that class. this was of course because almost everyone thinks they know something about music; you may not know or care or have done enough of the reading to be able to discourse on adorno or barthes, but you’ve surely got an opinion on 50 cent vs. kanye, whether toby keith is a racist, and if metal sucks or rules.

more than any of this motley crew of musos (or, as adorno would call them, the “retarded listeners“), i’ll remember this one girl who sat next to me, a plain girl who often wore tanktops. this girl was really kind of out of place; i think she failed basically every quiz and it was obvious that she had taken the class because she thought it would be an easy elective but was struggling with the reading. on the surface, we didn’t have much in common, but she was one of the few people in the class who wasn’t oozing with affectation and so was i, so we sat next to each other and made small talk occasionally. i wouldn’t even call us “acquaintances”: our relationship was a couple of levels below that. however, one day, about halfway through the semester, we had the conversation which basically everybody in the class was always waiting with bated breath to have, the “what kind of music do you like?” conversation. i would conservatively estimate that about 80% of the class had answers to this question well prepared in advance and that, on any given day, 20% of the class would be wearing t-shirts which could answer it without a word spoken. (personally, i was aching to describe my favorite song, sun ra’s “advice to medics,” as being like “god getting the high score on a pinball machine.”)

our music conversation was sparked by the end of the previous class, in which one of the heavily pierced graduate students convinced the professor to play a youtube video of some drone metal band (earth, maybe?) on the class’s big projection screen with the overhead lights off and the speakers cranked. the clip was really awesome and completely subverted my concept of what metal was, which i guess was the intention. anyway, in the next session, tanktop girl started a conversation with me by saying, “wasn’t that video from last class weird?” and i said, “yeah, definitely, weird.” and she said, “what kind of music do you like?” and i said, “oh, you know, a little bit of everything, how about you?” and she said, “umm…i don’t know, i like, uh, nickelback and creed.” and i said “oh, cool, i like some of their stuff. who’s your favorite band?” and she said, “um, well, if i have to say, my favorite band is probably everclear.” “oh yeah?” i said. “yeah,” she said, “i really like to listen to everclear when i clean.”

and then class started but i couldn’t concentrate on the professor’s postcolonial reading of brian eno because i was thinking about three things, in quick succession. first, the strangeness of the fact that her favorite band was everclear, that, in 2007, anyone‘s favorite band was everclear, that the music of everclear still existed outside of i love the 90’s, even. second, the fact that her favorite band was her favorite not because they had catchy lyrics or heavy riffs or were sonically experimental but because they were good music to clean to. not music for airports but music for kitchens, music for scrubbing countertops with basslines that you could still pick out over the whine of a vacuum cleaner. (a year later, when i started my first full time job, i found that i had stopped listening to music. the only time i really listened to it in any non-ambient way was in the mornings when i was getting ready for work and i would put on graduation while i ironed.)

the third thing i was thinking about was everclear and how i remembered them and how much i had loved them once. i remembered when their song “everything to everyone” came out in 1997 — i was twelve years old at the time and the song was all over MTV, my one and only source of music. in the moment, i remembered just how awesome that song was to me. listening to it now, i still think it’s a pretty perfect pop rock song — it has a singalong chorus, loud-soft-loud dynamics, a catchy riff, and some sonic icing on the cake (those weird slide guitar licks, the siren-y synth, the breakdown). i remember thinking back then that music couldn’t get much better than this.

however, twelve year olds are fickle (also, music could get much better than that). i stopped liking everclear a few months later when the third single from the album, “father of mine,” was released. “father of mine” depicted, over a chunky, catchy alterna-rock backing much like that of “everything to everyone,” lead singer art alexakis’s emotionally fraught relationship with his absent father. the hook of the song is alexakis singing, in a sweeter version of the cobain wail, “my daddy gave me a name” and then a call and response vocal screaming after him, “and then he walked away!” “father of mine” made me stop liking everclear for two reasons. the first one was that i couldn’t identify with the song. most pop songs express very universal feelings: in order to sell millions of copies, they have to. the more universal the feeling expressed, the wider the possible audience, the more “pop” the song. “father of mine,” though, was very specifically about what it feels like to have your father leave you — the song didn’t use this specific experience to illuminate a larger feeling of alienation or sadness or otherness, it was about what it was about. my parents had always loved each other very much and made it clear that they loved me very much so i couldn’t understand the song in any real way. the second reason why i didn’t like everclear anymore was that, even though i couldn’t understand “father of mine,” i could still feel it somehow and i didn’t like the feeling it gave me. i didn’t like “father of mine” was because it made me feel sad in ways i couldn’t express and i didn’t want a song to make me feel sad.

while the anecdotes about lorrie moore 2.0 and tanktop girl are completely and totally true, they’re also completely and totally an exploitation. i’m exploiting these people who i didn’t really care about at the time but who i am now choosing to find meaning in so i can define myself and write a blog post about it. i’m completely taking advantage of those who had the misfortune of sitting beside or flirting with a person who completely ignored them and blew them off at the time but whose memory saved them somewhere and now wants to make them represent something. in one of those interviews with radio host michael silverblatt that i’m quoting from throughout this post, david foster wallace makes the point that the one thing that we know is bad is pretension – everybody hates the pretentious asshole who thinks he’s smarter than everybody else and so nobody wants to be “that guy.”

but then the problem is if you are “that guy,” if you can recognize some element of that in yourself, then you try to compensate for it. instead of being pretentious, you trend toward the opposite pole, but when you get there, you have to deal with an equal problem, which is the authenticity fetish. it’s like hipsters and music — like, a hipster’s favorite singer either has to be some glitchy kraftwerk-inspired icelandic crunk diva or it has to be bob seger (and not the early ‘bob seger system’ punky stuff, you’ve got to mean “like a rock” as seen in those chevy commercials bog seger). there is the one pole and there is the other; there is either the pretension or the authenticity fetish, which is really just inverse pretension, pretension dressed in a john deere cap from target instead of a bespoke keffiyeh.

i am an authenticity fetishist and so i am going to post a snapshot of a page of misspelled comments for a youtube video as representative of the beauty of humanity and i am going to see this girl who unironically loves everclear as being some salt of the earth reminder of what is true and real and i am going to see this girl who copied a lorrie moore story as teaching us all something deep and powerful about the anxiety of influence. except now, i’m not seeing them as human beings anymore, i’m just seeing them as collections of those signifiers, as those images. and so there we are sitting at the proverbial authenticity fetish table, me and these forgotten girls who i am mythologizing but whose names i can’t even remember and with me there’s david foster wallace and the sweet old ladies from mrs. thompson’s and the just plain folks from the cruise and the gosh darn farmers from the state fair and we’re all sitting at this table (it’s a big table) and it’s uncomfortable.

(of course, i made my place setting at that table (to extend that horrible metaphor further) by writing the previous section. as mr. alexakis notes over in “everything to everyone,” “i think you like to be the victim / i think you like to be in pain / i think you make yourself a victim / almost every single day.”) (also, all my moral fiction flailing here is totally reminiscent of that episode of gossip girl in which dan, after he pisses off jay mcinerney, has the opportunity to write a short story for the paris review about chuck bass’s secret pain but decides in a really simplistic and adorable way that that to do so would be exploitative and immoral and so tells PR editor noah shapiro to shove it.)

MS: when you structure a book in this way, do you mean it to be discovered?

DFW: yeah, that, that’s a very tricky question, because i know when i was a young writer, i would play endless sort of structural games that i think in retrospect were mostly for myself alone, i didn’t much care. i don’t really — i mean, infinite jest is trying to do a whole lot of things at once…for me, uh, i mean a lot of the motivation had to do with it seems to me that so much of, um, premillenial life in america consists of enormous amounts of what seem like discrete bits of information coming and the real kind of intellectual adventure is finding ways to relate them to each other and to find larger patterns and meanings which of course is essentially narrative, but that structurally it’s a bit different um and since fractals are more kind of — oh lord — since its chaos is a little more on the surface, sort of its bones are its beauty, a little bit more, that it would be a more interesting way to structure. i — ok, now i’m meandering — but i know that um, that for doing something this long, a fair amount of the structure is for me, because it’s kind of like, you know, pitons in the mountainside, i mean, it’s ways for me to stay oriented and engaged and get through it, and i don’t think i would impose weird structures on the reader the way i would, say, ten years ago. does that make any sense?

MS: yes, it does. but I wanted to suggest, at least for me, that the organization of the material, whether or not someone leaps up and says “fractal,” or even has heard of fractals, seemed to me to be necessary and beautiful because we’re entering a world that needs to be made strange before it becomes familiar. And so it seemed to me that in this book, which contains both the banality and extraordinariness of various kinds of experience and banality of extraordinary experience as well, that —

DFW: and the extraordinariness of banal experience.

MS: yeah — that a way needed to be found, and it thrilled me that it seemed to be structural, that the book found a way to arrange itself so that one knew — you know, for the longest time you would be faced with these analogies. you know, when ulysses came out, people talked about its musical structures. when dos passos’s books came out, people talked about film editing.

DFW: mmmhmm.

MS: it seems very hard in the last period of years to find a new way to structure a book.

most people know ricky gervais for his two critically acclaimed television series, the office and extras. those shows are great but my favorite of his works are the hundreds of hours of radio shows and podcasts he’s been doing since 2001. the shows are a simple, three man affair: gervais, his collaborator stephen merchant, and a radio producer, karl pilkington. they aren’t particularly exciting or high concept affairs — they’re basically just the three guys in a room bullshitting around for an hour — but they’re kind of great because of that lack of content and artifice. it’s kind of like when you experience a piece of art that jibes really well with your sensibilities and you think, “wow, i wonder what it would be like to be friends with tina fey/calvin trillin/wale/etc.?” well, this radio show is a sort of representation of what it might be like to hang around at the pub with ricky gervais and his mates. don’t get me wrong: it’s a show, it’s performative, sure, but the medium of radio means that it feels much more intimate and personal than a reality TV show about ricky gervais probably could.

if you actually listen to any of the radio shows, something very quickly becomes clear: ricky gervais is their star in name only. the real center of the shows is karl pilkington. pilkington, the producer, is in his mid thirties, was raised on a working class housing estate in manchester, and has an iq of 83. his opinions and thoughts on basically any topic are strangely compelling: he seems like a cross between stephen wright and homer simpson, only british. his perspective and use of language are addictive and when he feels like it, he can tell an anecdote which straddles the funny/sad line as well as anything from the office (example). maybe 80% of the airtime of the radio shows features gervais and merchant prodding pilkington into offering his bizzare and idiosyncratic take on the world and then, once he’s delivered it, the two of them laughing at him for his weirdness/mocking him for his stupidity/calling him names like “you stupid manc twat.” perhaps 20% of the time pilkington will say something that’s so surprisingly genius or completely off the wall that gervais will recognize it and then praise him as a sort of idiot savant, a reservoir of plainspoken truth.

it’s important to note here that it’s very obvious that three men are close friends and so the constant insults hurled at karl seem basically to be all in good fun and are coming from people who love him. yet the tension between love and exploitation, between on the one hand showing your friend who you think is weird and interesting to the world and on the other hand the victorian freak show, is always an undercurrent to the ricky gervais show. in one episode in the show’s first season, for instance, ricky and steve surprise karl by revealing his GSCE results live on air. as i understand it, GCSE’s, of which there are no american equivalent, are tests that british students take when they’re fifteen and sixteen to decide if they can study for the next round of tests, A levels, which determine if/where students will go to college. karl left school at 15 to work in a print shop and so never took his A levels, but he told ricky and steve on-air that he thought he had taken the GCSE exams for english, math, physics, and art, and had passed a few of them. however, when the results are revealed, we find out that karl only took one exam, history, and that he received the equivalent of a D-.

learning about his failure clearly affects pilkington emotionally — he becomes even more depressed than usual and gervais and merchant, sensing this, reassure him and remind him that “it doesn’t matter.” yet if it doesn’t matter, then why reveal it live on the radio? why would gervais and merchant pull this sort of “gotcha” trick on someone who’s their friend? it’s kind of uncomfortable to think about. the revelation of the scores lead to a recurring feature called “educating karl,” in which, every week, karl did sort of book reports about historical figures (freud, hitler, rasputin, che guevara) which were as usual riddled with inaccuracies and his own particular spin, and, during which, as usual, ricky and steve mocked him for being stupid. in one episode, gervais tries to give karl the oxford dictionary of quotations but karl turns it down, and then, later, made to feel guilty by his girlfriend for not putting forth any effort to improve himself, he buys a children’s book of quotations which is filled with pictures of sesame street characters.

obviously, karl is not particularly interested in history or literature. he has some fascination with the sciences, which manifested itself in a short lived feature called “do we need ’em,” in which karl, enraged by the presence of some seemingly worthless creature like jellyfish or snails, would ask a scientist whether these animals could be removed from the earth without consequences. however, his main intellectual pursuit is his childlike fascination with freaks. for a time, one of karl’s recurring features on the show was “cheeky freak of the week,” in which he would describe a deformed person whom he had learned about during the week. these freaks would take the form of siamese twins or the “the pillow man,” who has neither arms or legs but only a torso. karl is obsessed with freaks — for a time, he carries around a book with pictures of and facts about freaks everywhere he goes. in one episode of the show, he describes watching the controversial 1932 horror film freaks, in which director tod browning cast people with real deformities and disabilities to play sideshow freaks. in addition, karl notes on multiple occasions that his all-time favorite film, which he’s seen many times and continues to watch over and over again, is david lynch’s the elephant man.

in “david lynch keeps his head,” his premiere magazine profile of david lynch, david foster wallace briefly discusses lynch’s casting of richard pryor in the film lost highway. foster wallace notes that the scenes starring pryor, “who’s got multiple sclerosis that’s stripped him of 75 pounds and affects his speech…and makes him seem like a cruel child’s parody of a damaged person,” are extremely painful to watch and “not painful in a good way.” he argues that lynch has hired pryor not as an actor but as a freak, so that his “grotesque infirmity” will “jar against all our old memories of the “real” pryor.” foster wallace finds this mean and morally wrong, but notes that “at the same time,” the casting of pryor is “thematically intriguing” and “symbolically perfect.” in other words, it’s a complete exploitation of a human being but it’s also a powerful artistic decision.

i can’t help but feel that ricky gervais played out some of his issues about exploitation and authenticity in art in his last television series, extras. even though extras doesn’t share the fake documentary aesthetic of the office, there are still a lot of ways in which the show plays with the line between fiction and reality. first and foremost is the presence of gervais himself. in one of the radio shows which was recorded before extras, annoyed by the fact that people always confused him with david brent, the character he played in the office, gervais says, “we share a face and a voice but that’s it.” he and his extras character, andy millman, share much more — they’re both actor/auteurs who create successful television shows that make them famous. in terms of performance, gervais abandons the wild physical comedy and vocal mannerisms of david brent to play a character that’s much more naturalistic — so naturalistic, in fact, it’s almost as if gervais doesn’t need to act in order to embody him. the character of millman’s best friend, maggie, is also drawn from life; she seems pretty clearly modeled on pilkington. her naively un-PC positions on race and gender and strange musings on hypothetical situations involving animals sometimes seem as if they’re transcribed directly from the radio show. when andy millman becomes famous in the show’s second series, he dumps maggie and finds a new best friend in british TV presenter jonathan ross, who became one of gervais’s real life close friends after the success of the office. in addition to all this, the show is filled with famous actors and celebrities (kate winslett, david bowie, robert de niro) playing themselves, or, more specifically, riffing on or tweaking some aspect of their public persona.

though not quite as bad as david lynch’s use of richard pryor (which is pretty disturbing, at least for this viewer), a subplot in season 2 of extras features the actors shaun williamson and dean gaffney, both d-list celebrities in the UK who are famous solely for their roles on the popular british soap opera eastenders. (i am getting all of this information from wikipedia, it’s a blog, deal with it) neither of them has found much success after eastenders: in 2007, williamson performed in a staging of aladdin in london, the same gaudy, low rent play that gervais parodies in an episode in season 1 of extras. in 2006, the tabloid the people reported that gaffney was on welfare and, in that same year, he also appeared on i’m a celebrity, get me out of here, a survivor-esque celebreality show much like the one that is parodied in the extras finale. in extras, gervais and merchant are using williamson and gaffney largely as the kind of richard pryor stunt casting that david foster wallace describes — the two men quite literally play themselves, remembering their former glory but unable to get acting gigs and so instead working with millman’s ex-agent in a cell phone store. their performances are good but also in a sense irrelevant — their roles in the show are so much more about who they are than what they do. they poke fun at themselves just like kate winslett and chris martin do but it’s different somehow — you get the sense that, say, samuel l. jackson can afford to fuck with his public persona as much as he wants to, that it’s a lark for him and all the other celebrities to come on and lampoon themselves. for williamson and gaffney, it seems like it’s not all fun and games, that instead it’s their lives and livelihoods at stake. like most of gervais’s comedy, it’s funny but it’s also sad.

for all ricky gervais’s formal innovation and authenticity play, though, i still couldn’t help but be disappointed by the extras finale. gervais’s performance is powerful, no doubt, but overall it’s a total crank turner ending. there’s quite an easy recipe to follow: one part howard beale’s “i’m mad as hell” monologue from network, one part candide deciding it’s better just to tend his garden, stir with the force of annoyance that people have with reality television, turnk crank on creative oven, bake until grey pellet forms, serve hot and indignant. i mean, just think of the plot of extras: the artist thinks he can “make it big” but has to “compromise his integrity,” and gets “chewed up by the system.” “corrupted by show business,” he finds that “money and fame aren’t everything,” that “success isn’t all it’s cracked up to be,” and so he “leaves it all behind,” rejects it all, modernity and culture and society, everything except simple human companionship. at the show’s end, gervais leaves the sickening plasticity of the big brother studio for the literal, classical pastoral — the final shot of the series is a clear, blue sky and the final scene features maggie and andy deciding to get away from london and go “to the sea.” crank, crank, crank; turn, turn, turn. even if it’s probably the “right” ending for the show, in terms of your standard dramatic arc, it’s also about as cliched as you can get. it’s so easy.

so forget extras, do you want to see a piece of really innovative television? okay, well, instead of andy millman’s fake rant about the horrors of reality television and his fake exit from the celebrity big brother house on extras, here’s 70s singer/songerwriter leo sayer’s real rant about the horrors of reality television and real exit from the celebrity big brother house. if you watch only one video in this entire post (although i hope you’re watching them all because i picked them out special for you), watch this one and watch it all the way through:

(EDIT – embedding is disabled, please click through)

here is my moral crisis: in terms of how good a piece of art it is, the video of leo sayer’s exit from big brother, is, i think, so much better than the fictionalized exit on extras. you couldn’t make it from a formula or recipe — it’s too suffused with strangeness and idiosyncracy. there’s a self righteousness to what leo sayer is screaming about the indignities of reality television that is very similar to andy millman’s network style screed, but it’s completely undercut by the absurd request he’s making about needing more underwear (underwear!) because he either can’t or refuses to clean his own underwear and also by the fact that his whole meltdown seems not to be precipitated by a moral issue (as in the fictional extras) but by the fact that he was going to be voted off of the show that night and couldn’t deal with the rejection. leo is screaming about this underwear, about how he won’t wash his own clothes because the house is dirty, and it should be funny but he’s so emotional that he’s almost crying and it’s just so sad, sad to see him struggling against this big, goony security guys in his dated leather jacket and poofy hair. in the extras finale, after millman makes his rant about celebrity culture and leaves the house, he meets with his agent, who is buzzing about how he and andy can capitalize on millman’s bravura monologue. the agent’s attempt to exploit the situation is foiled, however, by millman’s surprise exit “to the sea.” the satire is so easy – as an audience, it’s obvious that we hate this plastic blowhard caricature of an agent and so when andy leaves him in the lurch, we laugh at the buffoon, laugh at his frustration and scrambling, and we support andy, the hero and clear moral victor. leo sayer, after exiting the real big brother house, meets with a producer, a gentle woman who seems genuinely worried about him and not just for the sake of the show. she tries to talk to him about his situation in a quiet, calming way, yet he continues to scream and bark at her, to rage like a latter day raskolnikov. at one point, he even seems on the verge of physically attacking her before he’s stopped by a security guard. it’s all so ugly, so human, so complex; there are so many layers to it. it’s a powerful piece of television and, as a viewer, as an audience member, it moves me more and it’s what i want to see.

but what i want to see is fucked up. even though i’m responding in a positive way, even though i’m not laughing at this video and posting it to digg with the tag “OMG DUDE WANTS UNDERWEAR BAD,” even though i’m empathizing and trying to send waves of parasocial love leo sayer’s way, it’s still fucked up for me to be enjoying watching it. nobody has to get hurt in ricky gervais’s fictional big brother house but leo sayer does have to get hurt for me to watch him on the real big brother. that makes me sad because leo sayer is the singer and songwriter of my favorite song of all time and i don’t want him to get hurt. yet i’ve watched this video of what is probably one of the lowest points in his life four times while i’ve written this section and it gets better every time, more powerful, and it makes me feel and think more things and i want to watch it more and again and over and over.

karl pilkington, when discussing his freak obsession, always makes it clear that he’s not “having a go” at the freaks, that he’s not trying to ridicule or make fun of them by discussing their deformities and otherness. the thing he says that likes about the elephant man and about learning about freaks in general is imagining what it’s like to be them, what their lives are like, how they can exist in the world. in other words, staring at and discussing the oddness of “freaks” creates within him a feeling of empathy, a real attempt to understand what it’s like to be a different person. this is a good thing, right? but it’s a pretty fine line between looking and gawking, between using and exploiting. and that line becomes refracted and multi-dimensional when we consider the real costs of the reality fictions which fill our bookshelves and television screens. watching leo sayer makes me feel uncomfortable but in a good way — it makes me feel like i understand leo sayer a little better and like i understand myself a little better. for this understanding to happen, though, leo sayer has to go through this pretty horrible experience that makes him a fool. is that worth it? i don’t know. what’s the difference between empathy and a freak show? (i wish i had a punchline for that.)

DFW: you’ve got to realize, though, when like, you know, when you’re talking to somebody who’s actually written the thing, there’s this weird monday morning quarterbacking thing about it. because i know that, at least for me, — i mean i don’t sit down to try to, “oh, let’s see, how can I find a suitable structural synecdoche for experience right now?” it’s more a matter of kind of whether it tastes true or not…and michael pietsch, the editor, said — i think that he got like the first four hundred pages — and he said it seemed to him like a piece of glass that had been dropped from a great height. And that was the first time that anybody had ever conceptualized what was to me just a certain structural representation of the way the world kind of operated on my nerve endings, which was as a bunch of discrete random bits but which contained within them, not always all that blatantly, very interesting connections. and it wasn’t clear whether the connections were my own imagination, or were crazy, or whether they were real, and what were important and what weren’t. and so, i mean, a lot of the structure in there is kind of seat-of-the-pants, what kind of felt true to me and what didn’t. a lot of the — i did not sit down with, you know, “i’m going to do a fractal structure,” or something —

MS: mmm.

DFW: i don’t think i’m that kind of writer.

MS: so there aren’t diagrams? or the diagrams emerged as you went along?

DFW: uhh, well, i had — i mean, i’ve got a poster of a sierpinski gasket that i’ve had since i was a little boy that i like just because it’s pretty. but it’s real weird — i’m not, i think writing is a big blend of — there’s a lot of sophistication and there’s a lot of kind of idiocy about it. and so much of it is gut and “this feels true, this doesn’t feel true; this tastes right, this doesn’t,” and it’s only when you get about halfway through it that i think you start to see any sort of structure emerging at all. then of course the great nightmare is that you alone see the structure and it’s going to be a mess for everyone else.

the problem with all those nice people posting on their blogs about their love for david foster wallace is that they’re doing the same thing that he said is bad, the same thing that he said is, in fact, the “angel of death for literary art.” those people who posted all or part of that speech of his or who commented “this is water,” they’re crank-turners. they take some input, they process it, they redistribute it; copy, paste, post. if you see bloggers through the lens of david foster wallace’s view of literary art, they are exactly what’s wrong, they are the problem, not the solution; the symptom and not the cure. link blogs, those thousands of sites which exist to cover every subject under the sun, are crank-turning, nothing more, nothing less. the link blogger aggregates a series of links which he culls from automated RSS feeds and he posts them online with minimal or in many cases no commentary of his own. he’s not an author, he’s a librarian; he does not produce, he arranges.

in “e pluribus unam,” the essay which accompanied the “crank-turner” comments which i’m choosing to take wildly out of context and obsess over, david foster wallace focuses at length on a criticism of mark leyner’s my cousin, my gastroenterologist. in leyner’s novel, david foster wallace finds the apotheosis of what he calls “image fiction,” fiction which takes its MO, its SOP, from television. in image fiction and leyner’s novel in particular, david foster wallace finds writing which, though it has its charms, is ultimately “extremely shallow” and “dead on the page.” about leyner’s collage-y aesthetic, he writes:

when all experiences can be deconstructed and reconfigured, there become simply too many choices. And in the absence of any credible, noncommercial guides for living, the freedom to choose is about as “liberating” as a bad acid trip: each quantum is as good as the next and the only standard of a particular construct’s quality is its weirdness, incongruity, its ability to stand out from a crowd of other image-constructs and wow some Audience.

since this is, you know, an essay imitating a david foster wallace essay in order to criticize david foster wallace talking about how it’s bad to imitate other writers, i feel i should also mirror DFW’s takedown of leyner. if i had to choose my own text to epitomize the garbage and crank-turning of contemporary internet writing, i guess it would have to be the first thing i cited in this post, farhad manjoo’s december 18th slate article, “how to blog,” the piece which made such helpful suggestions as “don’t worry if your posts suck a little.” manjoo’s article is ostensibly about a recently released book, the huffington post complete guide to blogging. however, he notes that the problem with the book is that, to use his webby slang, it’s “dead trees,” a printed book not available in full text on the internet. therefore, he decides to recreate it inside his article. in other words, manjoo makes it his project to take a 240 page book and reduce it to a 1500 word “article” composed of bullet points and stray paragraphs, with an obligatory click-through to the second page to increase page views. if this is the new new new journalism, then i’ll stop my rhapsodizing about internet culture and join the doomsayers — we’re all fucked. despite the charms of wikipedia, google is making us stupid. i mean, this thing is the nadir of shitty blogging: it’s a listicle about how to write listicles! some totally random thoughts on this:

- just as a personal note, i hate lists. i’ve always loved books and getting books as presents but the one kind of book i hate to get as a present is the list book. you know, those books like “top 100 pop songs which feature the fender stratocaster” or “best american films of the last 12 and a half years” or blah blah blah blah blah. i hate those books, even the ‘llectual, high quality ones i’m supposed to like. a lot of list books are sold as “bathroom books” which strikes me as utterly disgusting — the idea that something being so simple and easy to read and divided, toilet-paper-like, into small, discrete sections could be a selling point is, to me, gross.

- something i find really funny and which i think deserves some kind of long form profile (maybe there was one and i missed it – send me a link and i’ll add it to the list!), is how the aforementioned mark leyner quit the world of avant garde fiction to cowrite a pair of bathroom books that have sold ridiculous numbers of copies and surely made him very rich.

- BONUS CONTENT: mediafire download of the audiobook of my cousin, my gastroenterologist. you can also hear leyner with bookworm’s michael silverblatt here (it’s definitely worth a listen, he’s a really good reader).

- mark leyner remembers david foster wallace.

- i think what i hate about lists is that they’re like reading for people who don’t like to read. because you don’t really read a list, you look at it, you scan it, you skim it. there’s no mimesis in lists, you can’t get lost in a list.

- a history of the music magazine listicle by michelangelo matos

- what gawker editor elizabeth spiers described as “one of the magazine world’s last great lame clichés” when she parodied one in 2003 (“Lists as articles. Listicles. (I feel dirty even saying it.”) has in 2008 become one of the main modes of content generation for gawker and for most other popular blogs. this is an obvious thing that i don’t even really need to say but my list is short and i felt like i needed another item so there.

- (online) dictionary definition of the word “listicle”

- a list of blogs which i was on a year ago!

god, i’m getting really pissed about lists! it’s kind of funny how heated up people can get about a formal or structural move in a piece of writing. it’s like, robbe-grillet, dude, i don’t care about the kiddy porn but your prose style is really pissing me off. public opinion of david foster wallace was a lot more divided before his suicide made everyone want to be his eternal best friend. it might be funny to think of it now, but back then some people genuinely hated the dude’s writing (hysterical, i know). i think some of that hatred didn’t just have to do with the content of his writing but had to do with a structural device, with his use of footnotes and endnotes. to think of it in a sort of reader response way, the demand that having to read those footnotes or endnotes put on a reader was taken by some people to be almost an affront — “you mean i have to use TWO bookmarks for this shit? that asshole!”

all of this kind of makes me think about kanye west. in his use of autotune on 808s and heartbreak, kanye west has found his footnote. just like david foster wallace, he’s taken this familiar formal device and foregrounded it, defamiliarized it. even though others had used autotune in a creative, non-transparent way before (just like others used footnotes before DFW), kanye uses it in a way that no one else has, his own personal way, all in the service of his art. this has caused a divisive reaction, even among people who already liked kanye. like david foster wallace’s footnotes, kanye’s warbling auto-tuned croon became a sort of litmus test. from the reactions i’ve read, it doesn’t seem like there’s much middle ground — either you think it’s a stunning creative move and a sign of him advancing as an artist or you find it makes him unlistenable and you wish he would get out those funky soul samples again.

and lest we forget, kanye’s not just a musician, he’s also a linkblogger! kanye west’s blog probably fulfills most or all of the criteria for a succesful blog that manjoo sets out in “how to blog.” in other words, it fulfills all the criteria of a crank-turning blog: lots of posts, some of the posts suck, it’s not literature, lots of pictures and videos. crank, crank, crank; turn, turn, turn. but even though it does all those bad things that i just talked about hating, kanye west’s blog is awesome. this is not just because of the celebrity factor which makes shaq’s twitter enjoyable; i would probably read kanye’s blog even if he was just some bedroom producer in chicago making shitty beats with a VST 808. kanye’s blog is what the extremely nerdy and subcultural blog boingboing purports to be: a collection of wonderful things. on christmas day, i woke up to his link to a video of “49 microwaves moved together to play jingle bells.” (“the only standard of a particular construct’s quality is its weirdness, incongruity, its ability to stand out from a crowd of other image-constructs and wow some Audience”) if you’re at all interested in art, fashion, music, celebrities, hot girls, gadgets or just random weird shit, kanye has you covered. it’s not just that, though, there’s also so much personality created by his selections and choics, the arrangement and aesthetic, and the one or two lines of commentary he adds to every post. i remember one day ‘ye posted a video of how to tie a tie and, in all caps, as is his way, noted something like “NO MORE CLIP-ONS.” it was adorable. i can decry farhad manjoo or the huffington post‘s stance on blogging, we could have this whole marcus/franzen style showdown, but it would all be for naught because i like link blogs and i read listicles every day and this kind of collapses my argument. i consider myself reasonably intelligent and well-read and i read kanye and kottke much more than i do the atlantic or the new yorker. the thing is, because of all the choice on the internet (“when all experiences can be deconstructed and reconfigured, there become simply too many choices”), i probably wouldn’t even know about this great new article in harper’s or new york without bookforum or some other linkblog to send me there.

MS: little bits of apologies for being smart. um, self —

DFW: or looking as if you’re trying to sound smart.

MS: yes.

DFW: which is — for me — i find what you’re saying flattering — um, but i think you’re overestimating some of the reasons — like this thing about the constant self-consciousness and apology. somebody at the reading in san francisco last night was very acute and made me very uncomfortable because she talked about the second essay in the book, which is this big thing about writing fiction when you watch a lot of TV and you live in this kind of very hip, ironic culture, and how hip irony can become toxic and blah blah blah — i won’t rehash the argument. but she pointed out that, you know, this essay makes that argument and then a great deal of the rest of the essays in the book employ a certain amount of hip, ironic self-consciousness that is, to me, that isn’t that attractive. And the apologizing for being smart, i think, can very easily become trying to head off the central criticism from you by acknowledging that i can get there first and deprecate myself so that you don’t get a chance to do it. and it’s very much of a piece with a certain kind of insecurity, what to me seems like a very american insecurity, that i have fully internalized, where i’m so terrified of your judgment that if i can show some kind of hip, self-aware, self-conscious judgment of myself first, i somehow am defended against your ridiculing me or parodying me or something like that — um, to the extent that i don’t think i’m the only person who suffers from it. i may be affective, but a great deal of it is, i think — that’s expressive stuff that i’m not comfortable with — i think a lot of that’s just a tic about my own psychology that i think my work would be better if there wasn’t quite so much of that in there. because it really is manipulative. i mean, it is acting out of terror of another’s judgment, and so trying to look as if he can’t possibly come up with a criticism of you having to do with how you appear that you haven’t gotten there first.

recently, i listened to the slate audio book club’s discussion of elizabeth gilbert’s eat, pray, love. this is despite the fact that i haven’t actually read the book (“i don’t listen to audiobooks. i prefer good literary podcasts to recorded fiction. with them, you get the novelists’ ideas as well as the critics’ thinking in one package.”). it’s not that i haven’t thought about reading eat, pray, love; i have — when i bought everyman, i almost bought a copy, but i was also buying the devil wears prada that day and i thought that buying both of them at the same time would make me seem really effete. (this is yet another example of how absurdly self conscious i am — i was afraid the korean cashier, who was a middle aged woman who very likely speaks no english, would, in the fifteen seconds that she was ringing me up be able to recognize the books i was buying, form a meta-aesthetic judgement based both on their combination and the relationship of that combination to me, and judge me accordingly.) anyway, i listened to a handful of the slate audio book clubs this winter and the eat, pray, love episode is by far the most heated i’ve heard. (this is totally like the part in a david foster wallace essay where he reveals himself to be a secret expert on dostoevsky or technical linguistics, but all i can talk about are slate podcasts and everclear.)

at the beginning of the episode, it’s obvious to the listener that club member stephen metcalf hates the book while member katie roiphe loves it, with the third member, julia turner, in between the two but mostly siding with roiphe. the episode proceeds with metcalf attempting to make criticisms of the book and roiphe shooting them down as being based mostly on his dislike of elizabeth gilbert’s personality instead of anything actual or true. the most interesting thread they get on to has to do with elizabeth gilbert’s rhetorical persona. the one point they can agree on is that that elizabeth gilbert is a very intelligent writer who has an incredible understanding of the conventions of her genre. both roiphe and turner note that just when they might find something ridiculous or annoying, gilbert would have an aside where she would say, like, “you’re probably finding this ridiculous or annoying” and so would absorb their criticism. metcalf sees this mastery of rhetoric as insidious and finds it disgusting that gilbert has, in his eyes, molded the truth so completely in order to make her “spiritual journey” saleable. however, roiphe sees gilbert as a master of a form who, sometimes despite herself, communicates very real things about life, such as, for example, how difficult it can be to meditate.

the tension between the two sides climaxes when metcalf, attempting to finally once and for all prove in an objective and new-critic way what he finds so abhorrent about the book, reads aloud a particulary new-agey passage in which elizabeth gilbert describes climbing to the top of a tower in her ashram in india to try to find, you know, transcendence. for all his attempts at neutrality, metcalf’s obvious disdain for gilbert seeps into his reading — his tone is incredibly sarcastic. after he finishes, roiphe and turner immediately disqualify his reading of the passage because of the way he reads it (roiphe, in a later episode about cormac mccarthy’s the road, a book she hates, goes on to do the same thing in an even more obnoxious way by pointedly reading out every piece of punctuation ).

by coincidence, the passage that metcalf reads so sarcastically in the slate podcast as an example of how much he hates eat, pray, love is the exact same passage that the youtubette embedded above reads sincerely as an example of how much she loves it. compare their readings:

we really don’t need to go into the impossibility of objective textual criticism and how both their readings of the book are equally valid, the death of the author blah blah blah blah blah. the larger point to take from this, i think, is that maybe that silly old anti-intellectual maxim is true: we don’t know what art is, but we know what we like, and what we like has a lot to do with squishy things like personality and emotion and feeling. it’s not whether vampire weekend’s guitar riffs are a repackaged appropriation of african music, it’s whether those appropriated, repackaged, exploitative, derivative guitar riffs make you rock out (gently, in the colors of benneton) (*). it’s not whether david foster wallace’s footnotes are a stunning avant garde gesture which are a perfect structural representation of contemporary information overload or whether they’re irrelevant and unnecessary crap that should’ve been deleted by the editor, it’s whether you like david foster wallace enough to want to read his footnotes. it’s not whether elizabeth gilbert really and truly had the neatly packaged revelations that she tries to sell you in her book, it’s whether those revelations are true to you and whether she is too. beauty=eye of the beholder.

like, the youtube girl that i’ve embedded above. on the one hand, she’s the most disgusting example of twee milleniality you can find. when describing that miranda july (!) book, she says “this book really made me…feel” and this is about the most incisive criticism she’s able to make in her entire six minute video. she notes that when she went to the bookstore, “there were a lot of books that [she] liked the ideas of.” she’s got the ridiculous contemporary nostalgia that my generation has for our youth: she belongs to a youtube group called “wemissreadingrainbow.” she’s a complete oversharer; i mean, for god’s sake, she can’t even read a book without posting a video about it online. on the other hand, as publishers and presses are shrinking and folding, who reads and who buys books today? her. she’s somebody that does. and not only does she read and buy books, she cares about them enough that she wants to share that with other people so that they’ll read and buy books, and she does all this even though she’s not the most articulate or insightful person in the world. that’s a good thing, that’s a thing that we need and should encourage.

of course, both readings are completely valid, we can mount cases and make arguments for each. in the end, though, it just depends on if you like her (i do — i miss reading rainbow, too!)

MS: …and “how do you take in new information and arrange it?” seems to be part of your subject.